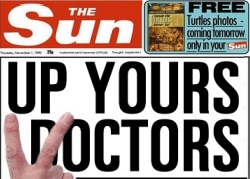

Despite the colour scheme, Bad Medicine is not a red-top, but sometimes a red-top headline doesn’t do any harm, unlike over-diagnosis and over-treatment. The campaign against the problem of meddlesome doctors, a problem that has been around for as long as there have been doctors, had a re-launch last week, guided by a collaboration – now there’s a modern word – between the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the BMJ. What was ‘Too Much Medicine’ is now re-branded ‘Choosing Wisely’, a title so generic it could apply to anything: at least with ‘Too Much Medicine’ you knew what they were on about. The language has become stifling, like the still heat of a tropical day. We are assured that ‘Choosing Wisely conversations will rebalance discussions’ between doctors and patients, who will jointly ‘be supported to acknowledge…that, sometimes, doing nothing might be the favourable option.’ Hullo? To you and me, that’s stick the drugs where the sun don’t shine.

Despite the colour scheme, Bad Medicine is not a red-top, but sometimes a red-top headline doesn’t do any harm, unlike over-diagnosis and over-treatment. The campaign against the problem of meddlesome doctors, a problem that has been around for as long as there have been doctors, had a re-launch last week, guided by a collaboration – now there’s a modern word – between the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the BMJ. What was ‘Too Much Medicine’ is now re-branded ‘Choosing Wisely’, a title so generic it could apply to anything: at least with ‘Too Much Medicine’ you knew what they were on about. The language has become stifling, like the still heat of a tropical day. We are assured that ‘Choosing Wisely conversations will rebalance discussions’ between doctors and patients, who will jointly ‘be supported to acknowledge…that, sometimes, doing nothing might be the favourable option.’ Hullo? To you and me, that’s stick the drugs where the sun don’t shine.

The general drift of this monumental mash-up of the English language is thus obscured. The re-launch went off like a North Korean rocket. Of the red-tops, only the Mirror noticed – hence Dr No’s attempt to fill the gap – but the broadsheets did cover the story, in various incarnations. The Guardian, shame on it, spun the story as back-door rationing (944 comments). The Telegraph (131 comments, 130 of them from ‘Right You Are’ of Tunbridge Wells) told its readers what all good Telegraph readers had known all along, that quacks are bad news and ‘do more harm than good’, adding for good measure a dose of Adam Smith: the quacks only do it because they get paid to do it. The Independent – no surprises here – did its best to flatten a dead pancake (8 comments).

Given that some doctors – not all doctors, some do the opposite, some even get it right – do over-investigate, over-diagnose and over-treat, shifting the sum product of their endeavours into the red, what is to be done about it? To tackle that question effectively – just telling them to stop over-investigating, diagnosing and treating won’t work – we need to ask: why it is that over-active doctors carry on as they do.

Here, there is no shortage of candidates. Consumerism, Dr Google and the rise of patient expectations, fuelled by the media hyping up medical breakthroughs; medical payment schemes that incentivise activity over inactivity; defensive practice brought about by the fear of the litigious patient; all these are up for interview. So to is Big Pharma, not just for manufacturing a pill for every ill, but also an ill for every pill. The numerologists, the ones who make astrology look like real science, nominate supply and demand. Other candidates include fashion based medicine – the notion that medical practice is more influenced by fashion that evidence; a hopeless grasp on the understanding of risk, not just by patients, but also by doctors; over-zealous medical charities that fumigate the populace with alarms about their own brand of medical horror; the patient’s willing faith in the magic of medicine; and, last but not least for general practice, where the vast majority of medical activity takes place, its historical roots on the high street and in the corner shop chemists, where the punter pays and the apothecary provides. The possible causes are indeed legion.

If there is one striking thing that emerges from this list, it is that the causes of medical over-activity appear to lie not so much in a conspiracy against the laity of doctors behaving badly on their own, as in an interaction between society, in its various aspects, and medicine – what we might call the medical contract. This contract, which has at times the appearance of a collusion of over-activity, is profoundly felt and deeply rooted. It tells us that the weed of over-activity – for if a weed is a plant growing in the wrong place, then medical over-activity is activity happening in the wrong place – will not be easily uprooted. Cut off the foliage while leaving the roots, and the weed will return. Telling doctors to stick their drugs where the sun don’t shine won’t work, the punters will just go elsewhere.

If Dr No had to single out candidate, he would suggest what he has previously called the statistical, or medical, fallacy, which is the notion that population statistics apply to individuals. The vast majority of both doctors and patients believe that this test, and this treatment, benefit this patient, when in reality most screened patients don’t benefit, many diagnoses were never going to kill the patient, and most drugs don’t work. On an aggregate statistical level, some screening tests and some drugs might work for some people – which is the rational for using them – but that ignores the swathes, often if not usually hundreds, of individuals screened diagnosed and drugged so that others might benefit. Were there no harms, the benefits might justify the costs, but the brutal reality is that there are almost always harms.

Buried in the waffle of Choosing Wisely, there is the kernel of a good idea struggling to be heard: caveat emptor. Instead of the consumerism of demand, ‘I want, I want, I want’, the wise consumer would do well to quit demanding and start asking, ‘what’s in it for me’. The answer to cutting medical over-activity lies not in curbing doctors behaviour, but in encouraging intelligent questioning by wary patients.

And yes, Dr No knows, pigs might fly. But they said that about humans until the Wright Brothers came along.