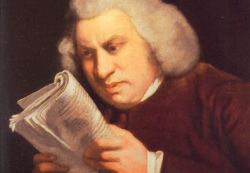

“Those who, in the confidence of superior capacities or attainments, neglect the common maxims of life, should be reminded that nothing will supply the want of prudence, and that negligence and irregularity, long continued, will make knowledge useless, wit ridiculous, and genius contemptible.”

“Those who, in the confidence of superior capacities or attainments, neglect the common maxims of life, should be reminded that nothing will supply the want of prudence, and that negligence and irregularity, long continued, will make knowledge useless, wit ridiculous, and genius contemptible.”

–Samuel Johnson: Life of Savage, 1744

Were it not a hideous truth, the comedically absurd case of the dehydrated patient who dialled 999 from his hospital bed to get a drink of water could have been a scene from Cardiac Arrest, the dark but for those in the know searingly accurate 1990s depiction of life and death on the wards at St Elsewhere’s. By a coincidence, Line of Duty, a police precinct drama in which the leads like Getting Things Done, not in the usual software way, but with hardware, much of it dark blue or grey and involving combustibles, is now running on BBC2. Both were written by Jed Mercurio, and both are about Mercurio’s mojo: the dark and bitter secrets that lie at the heart of two of our biggest institutions: first the NHS, and now the Police. If Cardiac Arrest was Line of Duty with stethoscopes, then Line of Duty is Cardiac Arrest with police badges. Even the protagonists, Andrew Lancel and Martin Compston, look the same.

Dr No digresses. Kane Gorny, the patient who dialled 999, soon died a wretched death, dehydrated and delirious. Last week, deputy coroner Shirley Radcliffe recorded a narrative verdict, but made it clear she believed Gorny’s doctors and nurses were to blame, ruling that neglect, incompetence, collective failure and a ‘culture of assumption’ all contributed to his death. Senior clinical staff at St George’s Hospital, Tooting, where the death occurred, laid conspicuously low, but did respond through their Comms Team, a outfit already (in)famous for spooking kidney patients via twitter, apologising for the death, but in the same breath lauded their apparently routine high quality healthcare, as if a thousand uncomplicated phlebotomies could atone for one horrid avoidable death. Sorry guys, it doesn’t: one horrid avoidable death is one too many.

One would hope that such terrible events were lightening strikes of great rarity, but it seems they are not. Earlier this year, Dr No saw first hand, again at a teaching hospital, a similar but in the event less pernicious – perhaps because he was on hand to kick ass and take names – culture of neglect, incompetence, failure and assumption. As a blogger, Dr No hears from others who have had similar, and often tragic, experiences. And then there are the now public tragedies: Mid Staffs, the ten tip-of-the-iceberg cases in last year’s report by the Health Service Ombudsman, and, in the last month, two more critical reports from Can’t Quite Cope. The lightening isn’t just striking twice, it is beginning to strike everywhere, as the decaying institutions of the NHS become conductors for bolts of malign mayhem.

A primary malaise behind this mayhem, it seems to Dr No, is that pernicious invention of modern healthcare, ‘the team’. Of course not all teams are bad, and some are very good, but nowadays pervasive generality of ‘team culture’, a pervasive generality we might note much encouraged by Stilton and his goons at the General Medical Council, and no doubt by the corresponding big cheeses at the Nursing and Midwifery Council, is the cultural mist that can mask a multitude of sins. The team culture encourages collective responsibility; but when there is collective responsibility, there can be no individual responsibility. The patient is no longer ‘my patient’ – a phrase Dr No grew up with, but which is rarely heard these days. The patient instead belongs to the team, and the team takes responsibility; but all too often that team is a misty abstraction, with the inevitable result that no one takes responsibility. As the collective mind focuses on passing the buck, so the patient falls through the cracks in the floor.

There has been some uncertainty about the moral thrust of Johnson’s ‘want of prudence’, with which he closes his Life of Savage. The common assertion is that his meaning was that no amount of ‘talent’ can compensate for moral torpor. Dr No inclines to agree, and furthermore considers it applies to modern healthcare: no amount of medical or nursing ‘talent’ can compensate for the moral torpor of team culture. It is the ‘neglect of the common maxims of life’ – that is, a reluctance to take personal responsibility for patients, despite ‘confidence of superior capacities or attainments’ – that can, and increasingly does, give rise to ‘want of prudence’, and so to avoidable lethal harm. As it happens, in their way, that is what much of Cardiac Arrest and Line of Duty are about – so perhaps Dr No wasn’t digressing after all.

Dr No should have made it clearer he too thinks the individual doctors and nurses have a lot to answer for; indeed the paragraph that starts “A primary malaise behind this mayhem…” starts with ‘A’ rather than ‘The’ for that very reason, and that sentence very nearly had a parenthetical clause (‘in addition to the manifest failings of the individual clinicians’). The only reason it didn’t get that clause was because he felt it added clutter, and he wanted to keep the focus on the negative effects of the ‘pervasive generality’ of teams. His premise is that the move towards ‘team-working’ dilutes individual clinical responsibility, and so directly facilitates the sort of slapdash ‘someone else will take care of it’ approach that appears to have dominated Gorny’s (lack of) care. The quotes A&E CN provides above (16 Jul 2012 11:03am) and further ones in the Telegraph article he links to (“One of the errors is you get into assuming other people have done that as part of a team.” “My role was just the operation, I thought that had all been sorted out and assumed everything had been put in place.”) do provide a strong suggestion that not only was team-working a smokescreen, it was also a direct contributory factor to the serious errors that were made. As the Dr Radcliffe the coroner remarked: “It seems to me there was a lack of ownership, and a lot of assumption.” Teams, it seems to Dr No, can be fertile ground for ownership-lite, assumption-heavy care, which is not in any way to excuse the individual clinicians, but it is to say that teams make it easier for the holes in the serious adverse incident cheese to line up.

The paper the WD quotes from and links to is worth a read – as is the NHS Choices website commentary on it which attempts to poo-poo the paper, opining that “Most of these ‘possibly preventable’ deaths occurred among elderly, frail patients with multiple other medical problems. This raises debate over whether these deaths were actually ‘preventable’.”

As if that blatant ageism wasn’t enough, the commentary then adds: “While a single preventable death is one too many, the researchers actually found that the number of preventable deaths was far lower than previously thought” – a bizarre attempt to spin the findings in a positive light, with further poo-poo mutterings (“main thing…is that these are estimates based on a relatively small sample”; “will still have been some subjective analysis”) in the conclusion…dear oh dear oh dear…

Anonymous on 16 Jul 2012 8:27pm – removed the double post – hope that is OK.

Thank you for removing double post, was computer glitch!

It would appear that nurse education has a lot to answer for as well, making nursing a degree educated profession hasn’t improved the knowledge of disease processes and medications apparently. There always has been a theory- practice gap, there is a big difference between learning signs and symptoms in the classroom and recognising them when they present clinically. I agree with Boots about the lack of clinical curiosity and use of assumption that lies at the heart of this. No clinician stopped to think WHY Kane had these symptoms.

There used to be a fairly rigid firm structure when on call. In my first housejob I was on call with the same SHO and Senior Reg and would be managing the patients with them with a daily ward round. It was clear that while I could ask for help that I had to present the case clearly and concisely with differential diagnosis and plan. They could shred the plan, but it certainly concentrated the mind.

Now the F1/f2 is infantalised and often given little more to do than a senior medical student in the olden days. In part this is cultural expectation, in part because the members of a team often only know each other slightly, due to the break up of the firm structure. It is impossible to have an EWTD compliant old skool firm system.

The expectation of the juniors is now that the decision will be made by a more senior person. The junior needs to survive only the shift and handover, more than likely the post take round will be someone elses problem.

And when was the last time anyone saw a medical student out of hours? We did the on call with the house officers, being both minions and fetching the curry, but were rewarded by great teaching of acute disease as a result. It was the highlight of the week being on call (and dare I mention being a student locum; something that would create apoplexy nowadays, but a great induction to the reality of medical life).

Boots

A&E CN – earlier comments crossed in the post. Dr No agrees the crucial point is the theory-practice gap. In say an exam situation, the clinicians would almost certainly know the correct answers – but they didn’t act on them in practice. The question, as you very correctly point out, is why not?

Medical education isn’t just about knowledge, it also includes the ‘socialisation’ into the prevailing clinical culture which these days is all about teams and pathways…could it be that the clinicians didn’t act because they believed the ‘team’ and ‘the pathway’ had everything sewn up, so to speak, this being a case with surgical elements? If true, that suggests that teams and pathways, instead of being part of the solution, might in fact be part of the problem.

In Dr No’s days as a junior doctor, there were teams (they were called firms) but they were vertical rather than horizontal, and there was a profound sense of individual responsibility at each level. The patients, in that sense, belonged to the consultant, the team and each individual doctor in that team. Dr No’s suggestion is that we need to return to that more traditional model.

Boots – what lies above was written earlier, and now given your comment, it seems we may be on the same hymn sheet. You have hit the nail on the head: junior doctors are infantilised. DN was struck while his mother was in the JR – another teaching hospital – by how childish the junior doctors were. It gave rise to DN’s characterisation of juniors as singing housepersons. These singing housepersons and their patients are the victims, but the villains are the edu-idiots who f*cked up medical education. Clare Gerada now wants to extend GP training to four five or GOK how many years. God help us all. DN has said all along – the way to learn is to do the job: more training (beyond what is needed) is just academics pissing in the wind.

Boots,

WD remembers affectionately the quality learning and indeed excellent patient care that took place during the “curry tutorials” in the doctors’ room on the ward when there was a lull on receiving nights. It takes a yesterday’s doctor to understand this important aspect of medical education. In todays culture, we would be seen as despicable slackers needing remediation.

She also remembers the deep “learning experience” associated with the sustenance provided by pink pudding and warm cheese scones!

http://witchdoctor.wordpress.com/2008/09/10/pink-pudding-and-warm-cheese-scones/

The deal with the curry was that the students picked it up, doctors paid and students helped chase all investigations and checked up on patients so that all free to eat in peace.

Good times!

Boots

That’s exactly what we need; to bring Sir/Lady [I know that was never in the films, but hey, modern times are here!:] Lancelot back!

Not the arrogance of Sir Lancelot, but the ‘leader’ of the team, the one who had the authority to make things happen and took responsibility for the decisions s/he made too!

Or, have you ever seen a ship sail without a captain?! … or a ship with two captains?! … or 10?!

Daft will only lead to daft, and that leads to chaos, and chaos is dangerous, and unsafe!

Sir/Lady Lancelot is the answer, bring them back … and with them, the curry too!

I’m not convinced that having a team leader or firm “boss” would necessarily have solved the problem in this case. Would a consultant orthopaedic surgeon present at the hospital necessarily have had a better understanding of Kane’s endocrine needs? Shouldn’t there be more provision in the UK of doctors who are specialised in general medicine?

For example, in the US, there is a whole specialism in Hospital Medicine. The “hospitalist” oversees the care of inpatients from commencement of care until discharge. Hospitalists are certified in Internal medicine and are not focused on one organ or one set of diseases but rather they liaise with all medical specialists, provide 24 hour cover and coordinate the care of the admitted patient. Hospitalists are also responsible for liaising with the patient and their family.

It is also worth bearing in mind that patients with rare endocrine diseases have to manage their diseases 24/7 for their whole lives when not in hospital. These patients may well have a better understanding of what they need than the doctors managing their care. Kane Gorny let doctors know repeatedly what he neeeded: better fluid management. Kane Gorny’s mother let the doctors know repeatedly what he needed: his medication. Both Kane and his mother were ignored.

A clueless team leader might just have easily ignored the patient’s requests for fluid, sedated the patient and treated the mother as a ‘neurotic woman’.

Anonymouser – all good points (especially about the dangers of not listening to the patient/relative, all the more so in rare conditions). It does seem to Dr No that a key weakness of Gorny’s consultants was that they perceived themselves as being part of a team, when what the patient needed was a single responsible individual. That single responsible individual doesn’t need (in fact can’t) be an expert in everything – just as the skipper on a sub won’t know all there is to know about the boat. He or she just needs to keep the overview, indeed command, and know who to call on when needed.

In the good old days, in Balint’s ideal world, that individual was the GP, whose roles included guarding against what Balint called the collusion of anonymity. The majority of today’s GPs are too busy trousering the easy money by weighing fatties, outing closet boozers and statinating the rest to have any time to look after their real patients. So the introduction of the ‘hospitalist’, not a very British way of naming things, or perhaps re-introduction, because in a way that was what the old general physician often did, seems like a excellent idea to Dr No. Just because it is American, it doesn’t mean it is a bad idea!

There difficult expectations now among – medical students are sent by taxi because it is too difficult to make a 20 minute train journey and navigate a 10 minute walk to go to a district general hospital near to their teaching hospital. I hear some newly qualified doctors indignant that they don’t go home at 5 p.m. and 3 years in discussing how disgracefully busy their jobs are and how they never intend to take a job that requires them to work past 5 pm. Clearly someone has promised something that their jobs can’t deliver. Fortunately the majority still try but it’s not a small minority. Not sure how as a senior to adapt to meet this new culture, but the continuity is gone which doesn’t help.

Where did this notion that young docs work to 5 then run home come from?!

I have three of them whom I sometimes hardly see because of regular work commitments! And they have friends, who come and visit all the time. Most of the time during these visits they talk amongst themselves about their training and how they have to stay way after, unpaid, to attend theatre with a consultant who operates late for example, or be on the wards because they needed more time for certain patients, or finish paper work, etc. Indeed, they always stay sometimes up to three hours even after a night shift because of patient management or for whatever reason. I think this particular one should not be allowed because it is dangerous for the young doctors specially if they have to drive home, but it is a regular happening! Remember the young woman doctor whose car swerved and hit a tree after a long night shift last year? What a loss of young promising life!

It’s all about morality as Dr No says, and I tell you, this is high among the young ones, despite working for peanuts too!

Dear anonymouse,

I do not think the young doctors that I work with and supervise are a bad bunch. Indeed one of the pleasures of being a Trainer is enjoying and being reinvigorated by their interest and enthusiasm. There are many positive aspects to the demographic changes in medical students of my day; and most have a healthier work life balance than I did (and perhaps still do have. Old habits die hard)

They are a different generation though, with some different values. your example of commutting when exhausted after a shift is illustrative. At a similar stage in my career I had to live in the hospital and work normally the next day after being on call. Rotations now mean that many of our Trainees commute from Big City University while on their attachment in my unit, they have spouses and lives elsewhere. The camerarderie and curry club mentality of the Doctors mess is history when Trainees cease to participate for very valid reasons with the social life of a unit. Often the isolation is self inflicted. The trainees that move to accomodation at our hospital get much more involved, and get much more out of the attachment.

It is hard to maintain the positive aspects of apprenticeship alongside the tick box educationalism and rigidity of modern training programmes. No one regrets the passing of the more negative aspects, and there were plenty.

Boots

I now there is a ‘big difference’ between your training and that of the young docs of today. If I may add to what you mentioned already; the bad long hours for example, at least you had wide training and that provided you with wide opportunity to match. You were also guaranteed a job with the completion of a CCT … no more for the blinkered lot of today! … no need to mention the pensions who will hit the young docs most, law pay, no proper ‘boss’ anymore … long list!

Besides, patients used to have named consultants and that was clearly stated on each bed, that was not only good for the patient and cheaper for the NHS, but it also encouraged ‘real’ team spirit and proper feeling of responsibility and accountability … I would love to see that come back and I would love to see training widened perhaps not as much as yours but to ensure that the docs of today are not going to end up as thoughtless, hence heartless machines!

The only way to do that is to bring Sir Lanselot’s name on the patients beds, and on her/his trainees again! NHS needs to go back to basics, because that worked …

I don’t think this is just a medical thing and if you want to change it, you’re up against changing the prevailing culture in society. Want a bank loan? Don’t call your bank manager – you won’t even be able to find his number – call an anonymous call centre with people reading from a script and eager to get you off the phone because there’s a big illuminated board on the wall telling them the average call time and the length of the queue.

I’m registered with an NHS dentist. I see a different one every time. My cat sees a different vet every time. The Royal Mail keeps rotating the posties around and as for the buck-passing mazes that call themselves the DWP and HMRC, it doesn’t take long to lose track of who you’re talking to let alone who might ever be persuaded to own your case.

It would be lovely if doctors led the fightback against this culture but do you have the energy whilst swamped with changes to the NHS?

No, just resting…and watching…

I know you’ve got your feet up, but I thought this might tickle you

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2206569/Dr-Una-Coales-Dont-act-gay-senior-GP-tells-trainee-doctors–youre-Asian-try-sound-Welsh-Scottish.html

So has this blog bitten the dust …..?

Interesting piece in the Mail. Una seems to be advising how to suceed despite unfair descrimination by examiners. This may be not as good as tackling predjudice head on, but I think unreasonable to use as a method to hound her out of the College. She clearly has enemies there.

I am glad that you are well and resting. It has been a quiet summer in the blogosphere, though a hectic one for me elsewhere. Keeping chaos at bay difficult at the moment, and much needless distraction in revalidation etc.

Boots

There’s a “big difference” when you compare the education you ahd and that of the newer generation of doctors. Actually, I’d say long hours, and you wide opportunity to match. A guaranteed job was also amazing just for completing a CCT. It certainly beats going to phlebotomy school.

I’d say I’m glad for you. Well done and all the best.