The Orwellian coup of calling the corporate bodies that run the NHS ‘trusts’ – with the comforting overtones of propriety and trustworthiness – hides the fact that underneath the surface they are like any other corporation: selfish, secretive and psychopathic.

The Orwellian coup of calling the corporate bodies that run the NHS ‘trusts’ – with the comforting overtones of propriety and trustworthiness – hides the fact that underneath the surface they are like any other corporation: selfish, secretive and psychopathic.

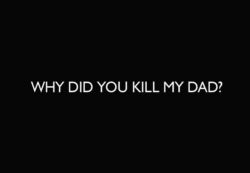

Dr No was brought to this cheerful observation by a dull but worthy documentary aired by BBC2 last week. Fronted by a man with a puffy dial whose every alternate sentence started ‘I wanted to find out…’, Why Did You Kill my Dad? was an over-scripted attempt to, err, find out ‘the true scale and [human] cost of killings by the mentally ill in Britain today’.

Unsurprisingly, it turns out that there is a lot more of it about than official statistics suggest. Chronic under-reporting – caused by basing figures on perpetrators rather than victims: one mentally ill person killing two people counts as one case – hides perhaps fifty percent of the ‘real’ estimate of 100 or so such killings a year.

That is two people killed on average every week in Britain by mentally ill offenders. Julian Hendy, who made and presented the film, and whose dad was one such killing, was suitably concerned. Dr No agrees: even one such death is a death too many.

Hendy somewhat dampened his powder by wheeling out a collection of grieving relatives whose clearly scripted replies had a habit of trying to pop out before Hendy popped his equally scripted questions. The usual suspects came to light. One constant theme was stone-walling by the NHS trusts responsible for ‘caring’ for the mentally ill offenders. The police, in contrast, were praised for making strategic use of Interflora.

At the start, Dr No, assumed the ‘you’ in the film’s title was the mentally ill offender, and, as a doctor, he naturally found his sympathies lay with the need to protect confidentiality of the patient – the mentally ill offender, that is, rather than the victim who, after all, was now an ex-patient. However dreadful the crime, the perpetrator remained a patient, and patients deserve confidentiality.

But, as the film progressed, Dr No found himself questioning his earlier assumption. A grieving relative made it clear his anger was not directed at the mentally ill offender, but at the trust that had failed to manage the patient adequately. The ‘you’ in the title, it emerged, was not the mentally ill offender, but the trust that had so horribly failed both victim and the mentally ill offender.

And the trusts were behaving just like any other body corporate faced with serious allegations. Sphincters tightened, shutters went down, and secrecy reigned. The usual litanies of ‘Inquiries’, of ‘Lessons Learnt’ were trotted out. And – in true psychopathic fashion – they not only lacked conscience and empathy, they did as they pleased, and violated expectations without guilt or remorse.