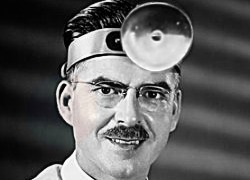

Dr No has Boots down as an otorhinolaryngologist – an ear nose & throat surgeon, but then the Greek always sounds better in the plush of private practice. These are the chaps who mount CDs on their foreheads, the better to peer into your orifices. Quite why the tonsil baggers need to mount a CD on their forehead to see what they are doing baffles Dr No. Gynaecologists seem to manage very well, without resorting to shining Abba’s Greatest Hits up the old hoo ha.

Dr No has Boots down as an otorhinolaryngologist – an ear nose & throat surgeon, but then the Greek always sounds better in the plush of private practice. These are the chaps who mount CDs on their foreheads, the better to peer into your orifices. Quite why the tonsil baggers need to mount a CD on their forehead to see what they are doing baffles Dr No. Gynaecologists seem to manage very well, without resorting to shining Abba’s Greatest Hits up the old hoo ha.

One might suppose all that peering through CDs might narrow both mind and vision, but Boots has clearly escaped a constricting fate. He has cast his surgical presence wide on the Borsetshire stage; and few indeed are the pies that have escaped the Boots finger. He is very bright, reads widely, and has the natural gift of synthesis to Boot. And so it is that when we come to survey his blog, we find well crafted posts, always finely written, invariably most interesting.

So it was with mild surprise that Dr No saw that Boots had, in a recent post, linked Dr No to ‘medical truancy’, which he described as one of ‘Dr No’s terms’ – despite the fact Dr No has made it quite clear that it is not one of his. A hazy sense of Boots being up in the air, possibly even on the other foot, drifted over Dr No. Not only does he consider the term not his, he actively dislikes it, and so feels a natural but gentle urge to put the record straight. And, happily, doing so provides an ideal opportunity for Dr No to, as we are wont to say these days, deliver on an earlier remark of his that ‘[medical] truants are a post for another day’.

The reason Dr No dislikes the term medical truant is because it carries an overlay of disapprobation. Boots himself in his post has medical truancy holding hands with ‘Lack of Moral Fibre’. The medical truant is tainted as a coward, a weakling unable to stand the heat in the kitchen – or perhaps even worse – a bunker off, a skiver. Now: how right and fair is it to tar a doctor without a practice with these harsh brushes?

The OED defines a truant as ‘a lazy, idle person; esp. a child who absents himself from school without leave; hence fig., one who wanders from an appointed place or neglects his duty or business’. Laziness, idleness, absenteeism; even – horror of horrors! – neglect of duty: a full house of Old Testament fury to be flung on the heads of those who truant! And, on the face of it, we cannot deny that the doctor without practice is absent from the profession, and so, it would seem, is a truant.

But, if we care to remove ourselves from the moral high ground, and look more closely at the meaning of truancy, we see that it has its roots in obligation: obligation to attend school, an appointed place, or to one’s duty; and truancy is the act of neglecting these obligations. And so it is that, in the absence of obligation, there can be no truancy.

No such obligation can fall on the involuntarily unemployed, for no one has an obligation to attend work that they cannot get. These indeed are the lost souls of the lost tribes, medical exiles, condemned to long for a lost profession. To taint these tormented beings with the tar of truancy is indeed a harsh and baseless cruelty.

But what about those who have chosen to exclude themselves from the profession, perhaps to seek a sunnier prospect, or because they have passed their private Rhett Butler Moment, and now know that the lover that once called to them so strongly is today no longer for them? Have they, in exercising that choice, dissolved the ties – if they ever existed – of obligation? Or could it be that those all too real ties of obligation, knotted now into harsh whips of punishment and disapproval, have now come back to haunt them?

Hacksaw and her descendents will naturally see the matter through the prism of the till. Medical students ring up a quarter of a million pound bill on the tax-payer by the time they qualify, and so, the argument goes, they have a duty, an obligation, to pay back that investment by the tax-payer, to the tax-payer, by practicing medicine.

But this argument has more holes in it than the coalition. Hacksaw herself studied chemistry, but felt under no obligation to spend all her life playing with Bunsen burners. Not all psychology graduates practice psychology, nor all art graduates paint or sculpt. No degree is a contract of obligation, a straight-jacket, to a single career. Indeed, were it so, we could happily rid ourselves of all those LLBs that litter parliament, and return them to their Dickensian cupboards, so that they too might repay in kind the expense of their degree, and their debt to society. But we do not, and equally, we cannot reasonably compel a medical graduate to follow a medical career.

The second origin of medical duty arises not in the counting halls of the banks, but on a higher plane. Doctoring, we like to believe, is a vocation, a calling, just as it is for the priesthood; and before we know it an almost divine thread of duty threads itself through the conduct of those called to these ancient and special duties. And so it is that we reserve special censure for those who have been called, and have yet rejected that call; and so too for those wayward souls who, once called, have since cut the ties of obligation, and so severed the thread. For it is distressing to discern that those on whom we may rely on in our of need may yet themselves have lost their faith

Now – be all that as it may – a second look at what is going on here reveals that these emotions, potent as they are, have their origin not in the wayward priest or doctor, but in the observer who, discomforted, responds by projecting that discomfort onto the hapless wanderer. The wanderer, unobserved, may feel the occasional pang of guilt or regret, but not necessarily so; they are more likely to breath great sighs of relief; and say to the observer: ‘the displeasure is all yours’.

‘And, frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn.’