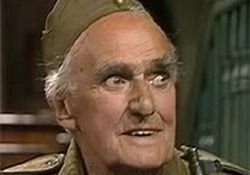

One of the factors that is said to underpin the ‘no change is not an option’ need to reform the NHS is our ageing population, the so-called grey tsunami, or demographic time bomb. This all party political IED is sitting there, we are told, with a short and inextinguishable fuse. If we don’t do something now to counter it, then we are all, as Frazer would have put it, doomed. But are we? Captain Mainwaring and his platoon survived any number of Frazer’s doom-laden predictions.

One of the factors that is said to underpin the ‘no change is not an option’ need to reform the NHS is our ageing population, the so-called grey tsunami, or demographic time bomb. This all party political IED is sitting there, we are told, with a short and inextinguishable fuse. If we don’t do something now to counter it, then we are all, as Frazer would have put it, doomed. But are we? Captain Mainwaring and his platoon survived any number of Frazer’s doom-laden predictions.

Dr No rather suspects that this alleged time bomb is indeed more political wheeze to panic us into accepting the ‘necessity’ for ‘radical’ reform – opening up the NHS to private service providers, and inevitably in due course private funding – than reality. Let us for a moment consider some of the alleged ‘facts’.

First and foremost we have the fact that our population is ageing: people are living longer, and so there are more older people. This is undoubtedly true – but the fact is it has been undoubtedly true for decades and yet we have not succumbed to a grey tsunami – because there isn’t one. Median age – the standard measure of population ageing – has been rising slowly but steadily – more gentle tide than violent tsunami – for the last several decades, and we are still afloat. Nor is there a prediction of a sudden increase – the alleged tsunami – in median age; if anything the rate of increase (line gradient) shows a slight decline. So – no time-bombs ticking away there. There is no reason to expect that we will not continue to accommodate the gentle rise in median age over the next fifty years, as we have done over the last fifty years.

The second stick of dynamite in the alleged bomb is the so-called old age dependency ratio, which measures the number of old (over 65) people ‘supported’ by working age (16-64) adults. This ratio is indeed set to rise alarmingly, but it is a measure of such astonishing crudity as to be woefully misleading. It assumes, for example, that all those aged over 65 are dependent – which is patently not the case. Furthermore, it excludes children, (and so total dependency); and as a population ages, so there is a corresponding decline in the number of children, and so a freeing up of resources (children are expensive, both in healthcare and education) available to care for the truly dependent. UN data for the period 1950 to 2050 – charted here – suggest that while old age dependency has risen and will indeed rise, corresponding declines in child dependency mean that total dependency has also risen, but notably less so (by only 38%, compared to 150%, between 1950 and 2050).

And this is where it starts to get interesting. If our GDP per capita (average wealth per person) matches or even exceeds the growth in ‘dependents’ then we have little to fear – the extra income will cover the cost of the old and grey. As it happens, our growth in GDP per capita has done rather well – apart from the recent dip caused, ahem, by recent political habits. There is – if we chose to use it so – more than enough extra money swilling around the system to pay for the Gilberts and Biddies.

Of course, the GDP growth bubble might burst; and Dr No hasn’t even begun to consider the other side of the equation: do old people ‘add value’ – that is, contribute, economically and socially, to society. He suspects they might. But the Tory (and other major parties, and all those tiresome blog commentators who drone ‘no change is not an option’) suggestions that ‘wur doomed’ does sound more like politically-minded Frazers egging Jones on. Dr No is more in step with Wilson: ‘Do you really think that’s wise, sir?’