Dr No’s mother has been admitted to hospital – at home. This NHS wheeze is a worthy idea, which Dr No supports. On paper, it is win-win: patients stay in their beloved homes, and the NHS saves money. In practice, it has one minor but fatal flaw. The hospital has a matron, kit in abundance, OTs, you name it, but no ward nurses. It is a hospital without nurses on its wards, and like all hospitals without nurses on the wards, it doesn’t work. Ironically, the money saved by not admitting patients to real hospitals could fund these nurses, but no one in the NHS has spotted this, and so the idea remains worthy, but doomed to fail. One supposes that were Crippen still blogging, he would have done hospital at home full justice, as he once did for another NHS corker, the hospital at night, a hospital whose defining characteristic was not an absence of nurses – rather the opposite in fact – but an absence of doctors.

Dr No’s mother has been admitted to hospital – at home. This NHS wheeze is a worthy idea, which Dr No supports. On paper, it is win-win: patients stay in their beloved homes, and the NHS saves money. In practice, it has one minor but fatal flaw. The hospital has a matron, kit in abundance, OTs, you name it, but no ward nurses. It is a hospital without nurses on its wards, and like all hospitals without nurses on the wards, it doesn’t work. Ironically, the money saved by not admitting patients to real hospitals could fund these nurses, but no one in the NHS has spotted this, and so the idea remains worthy, but doomed to fail. One supposes that were Crippen still blogging, he would have done hospital at home full justice, as he once did for another NHS corker, the hospital at night, a hospital whose defining characteristic was not an absence of nurses – rather the opposite in fact – but an absence of doctors.

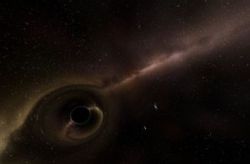

Meanwhile, various fragments of the NHS drifted in and out of Dr No’s mother’s orbit, like asteroids flying through space. Occasional comets flared, like the excellent OT who knew her job, and was good at it. But there was also a lot of dark matter. A potentially lethal combo of GP, pharmacist and ‘helpful friends’ contrived to give Dr No’s mother an overdose of morphine; she was lucky to escape with only nasty side effects. At every turn, health and safety rules threatened the real health and safety of the patient. But the most toxic encounter of the last week came from an unlikely source: a district nurse.

Dr No’s mother has had for some time stubborn leg ulcers. In such patients, managing these ulcers is more a running battle against running sores than a project to cure. Early battles conducted by the practice nurses were lost, until Dr No intervened and told them to stick their antibiotics somewhere useful, like in the bin, and his mother to elevate her leg. As if by black magic, the ulcers got smaller. The district nurses at this stage declined to be involved, claiming that if the patient could get to the surgery, even if it needed a blue light convoy to get her there, then she did not meet their ‘referral criteria’.

Then, somehow, Dr No’s mother got on the district nurses’ books. How this happened is a complete mystery, and is no doubt currently the subject of an untoward SEA by the district nurse managers. Be that as it may, clipboards arrived, boxes were ticked, and more care plans than you can shake a fist at were drawn up. Amongst the care plans was one that addressed the ulcers.

Although most leg ulcers in elderly patients are caused by venous disease, some are caused by arterial (or ‘mixed’) disease. This matters, because the most effective treatment for venous ulcers, compression bandaging, is contra-indicated in arterial disease, as the pressure from the bandaging can further impair the blood supply, causing gangrene and, in time, bits to drop off, or require amputation.

The clinical distinction between arterial and venous disease is not, bar barn door cases, a black and white matter. A blood pressure test, the ABPI, can help diagnosis, but it is far from perfect, and in sensitive elderly patients the conduct of the test itself can be problematic. Dr No’s understanding, from what his mother told him, was that the test had indeed been problematic, and the result inconclusive. Nonetheless, the district nurses knew, with the certainty that can only come from a clipboard, that the ulcers were arterial, and so compression bandaging was out of the question.

Dr No’s clinical hunch, based on the history and clinical signs, was that the ulcers were in fact venous. Being a hunch, it wasn’t a big issue, and he merely resolved to mention the question of diagnosis at some point; in particular, what the actual result from the ABPI test had been.

That point arrived on Friday. A district nurse appeared, as if teleported in from the cosmetic counter at Debenhams. Boy, did she do efficiency! And, Boy, did she do evidence! Everything, from the buckle on her belt to the bandage in her hand, was evidence based. The number, length and site of the strips of tape holding the end of the bandage were evidence based. Dr No suspected even the cosmetic counter smile was evidence based.

With so much evidence floating around, Dr No broached the subject of evidence for a diagnosis of arterial disease. It is important to note that he did so in a spirit of open and collaborative enquiry. At best he only had a hunch; nothing concrete to go on. So he asked about the result of the ABPI test, which, on his mother’s account, had been inconclusive.

And, Boy, did Dr No get steam-rollered with evidence! Who the hell was he to impugn evidence! The evidence based smile got harder, the evidence based glare more withering. Poor, deluded non-evidence based meddling son! She crushed Dr No with the weight of her evidence. Dr No retreated, bruised and shattered: an open enquiry had got him kicked hard in the emotional balls. His fragile resilience, in the face of all that lies before him, was damaged by a clumsy, brutal nurse.

This, then, is the nature of evidence based practice. Like the mass of a dark star, the weight of evidence becomes all consuming. Like a dark star imploding, the evidence based nurse implodes under the colossal weight of her evidence. No human light or warmth escapes. The nurse becomes, like a dark star, a dark nurse.